Everybody craves salvation. We have a universal need for a scapegoat, for a victory, for someone to tell us “everything will be just fine.” We like to shift responsibility for our evils to something — or someone — else, let them take the blame and put out the fires. The root of most religions lives in the hesitation to confront our reality head on. Why believe that war is determined by who is barbaric and wealthy enough to win, when we can believe it’s about whose side the gods are on? In this vein, religion has historically served as the backdrop for art, ranging from the depiction of deities in prehistoric cave drawings to the painting of Jesus hanging above my grandmother’s door.

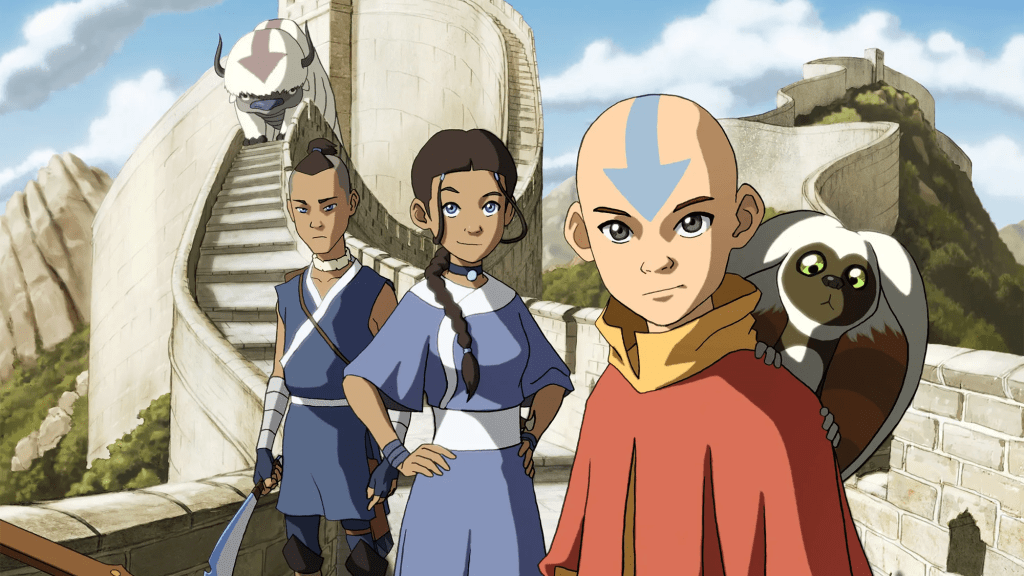

As humanity evolves its expression and artistic format, so too does it change the ways we navigate our reverence. Namely, the depiction of deities or religious saviors has jumped off the 2- or 3-dimensional format of painting and sculpture into the 4th dimension: time. The use of film has granted our saviors the gift of storytelling, most notably in the use of Christ figures. The first ever depiction of Jesus Christ in a film was in 1897, in the French short film “La Passion du Christ,” but most since then have been more subtle biblical allusions. We have increasingly observed these biblical stories in children’s media, helping to teach young audiences about morals, relationships, and sacrifice. In my opinion, there are few examples better than Aang, our protagonist in the animated series “Avatar: The Last Airbender” (2005).

New Testament, Same Story

DiMartino and Konietzko’s hit children’s series of the noughties captures a nuanced story mirroring Jesus Christ’s life in the ministry as a religious leader, gathering followers and building up towards his crucifixion in a way that children can understand and even relate to. Our protagonist features tattoos that resemble the placement of stigmata, a crucifixion at the climax of his story, and a clear message of sacrifice and salvation for the people of Earth. Aang’s journey throughout the series is chock-full of parallels to Jesus’s own story in the Bible, so let’s start with the basics: who’s who?

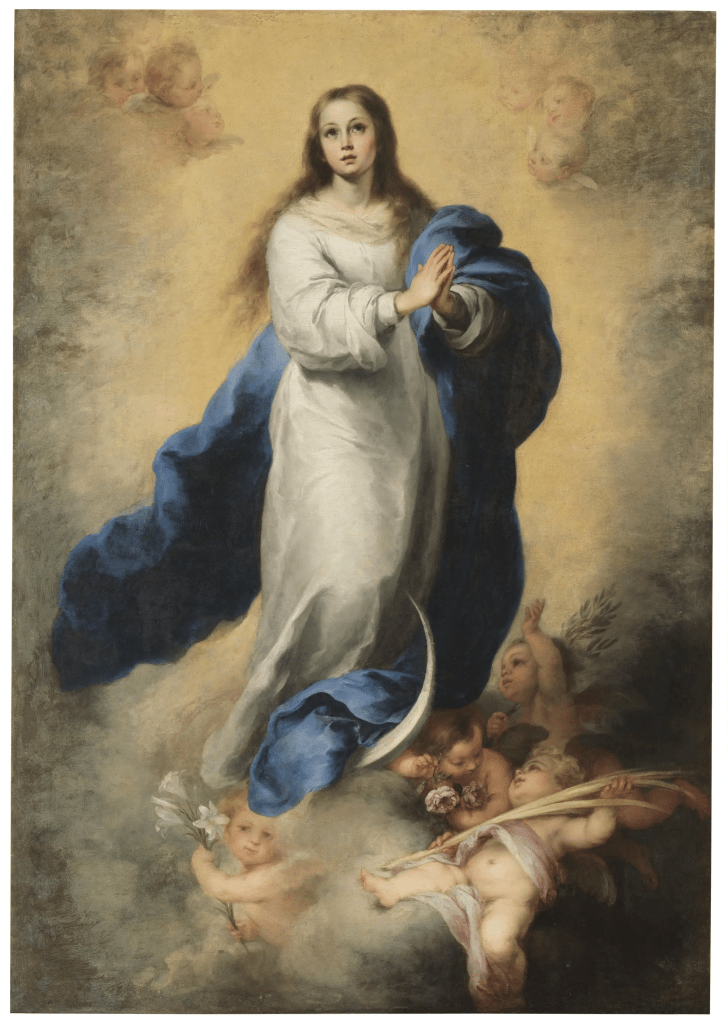

We’ve already established that Aang is Jesus, but it’s clear that the gang serves as his apostles. Of the twelve apostles, three were part of a smaller circle with much closer relationships to Jesus: Peter, James, and John the Beloved. Peter, originally named Simon, known for being impulsive, bold, and loyal, is resident earthbender Toph. Not only does she mirror the intensity of this apostle, but her position as the “muscle” of the group further establishes this parallel. Not to mention, the name “Peter,” given to him by Jesus, literally means “rock,” as he is meant to be the rock of the early church and maintain a strong sense of Christ’s teachings. Sokka, always the man with the plan, is James. Known for being ambitious, zealous, and passionate, James is brought to Jesus’s service by his sibling and is the first apostle to be martyred for his faith. With the same verve as this apostle, Sokka is the member of the gang always willing to take one for the team to further Aang’s mission. Finally, Katara, deep in her unyielding faith in Aang and willing to support even the most difficult moments, serves two roles: John the Beloved and The Virgin Mary. Brother of James and the one who brought him to Jesus’s service, John is often cited as having been Jesus’s closest friend, the only apostle at his crucifixion, and the only one not to die a martyr. Mary, traditionally depicted in paintings wearing blue and white, births the son of God, defined by her purity of heart, innocence, and love. She watched as her son suffered through the Passion. Katara, who is Aang’s first and most faithful supporter, remains at his side throughout the entire series, mothering and caring for the other children after having lost her own mother, and is notably the only one of the gang to be heavily featured in the spin-off series “Legend of Kora,” further evidence of her long and fulfilling life as a reward for remaining at the Avatar’s side.

The Immaculate Conception of El Escorial by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Contrary to the more direct parallels in the apostles’ relationships, Zuko serves as a reverse Judas figure. He starts his relationship with Aang as a traitor and uses him as a tool, just a means to an end for his long forsaken honor. By the end of the series, though, he is a devout follower, a disciple. Zuko’s life is framed by betrayal: he “betrays” his father when undermining his power, he betrays Uncle Iroh after receiving nothing but unconditional love and support, and he betrays Aang every chance he gets.

With our characters set up, there are further ways yet to highlight our biblical storyline. Our Christ figure Aang rises at the moment when humanity needs him most… kind of. He’s disappeared for 100 years, leaving the Fire Nation an opening to invade and destroy communities all over the world. As the point of no return nears, Sozin’s Comet, Aang rises from his iceberg, beginning his journey already fit with some Christ-like traits. We meet Aang the airbender, an element known for being evasive, defensive, and rarely used for attack. He is a young monk who practices pacifism and stoicism, even fit with his monk’s tattoos that mirror the placement of stigmata, framing his head, hands and feet. As the series progresses he gathers supporters from across the world, starting with his first, most loyal apostle, Katara. He builds up bending experience, performing miracles for the towns he visits whether their problems are large or small.

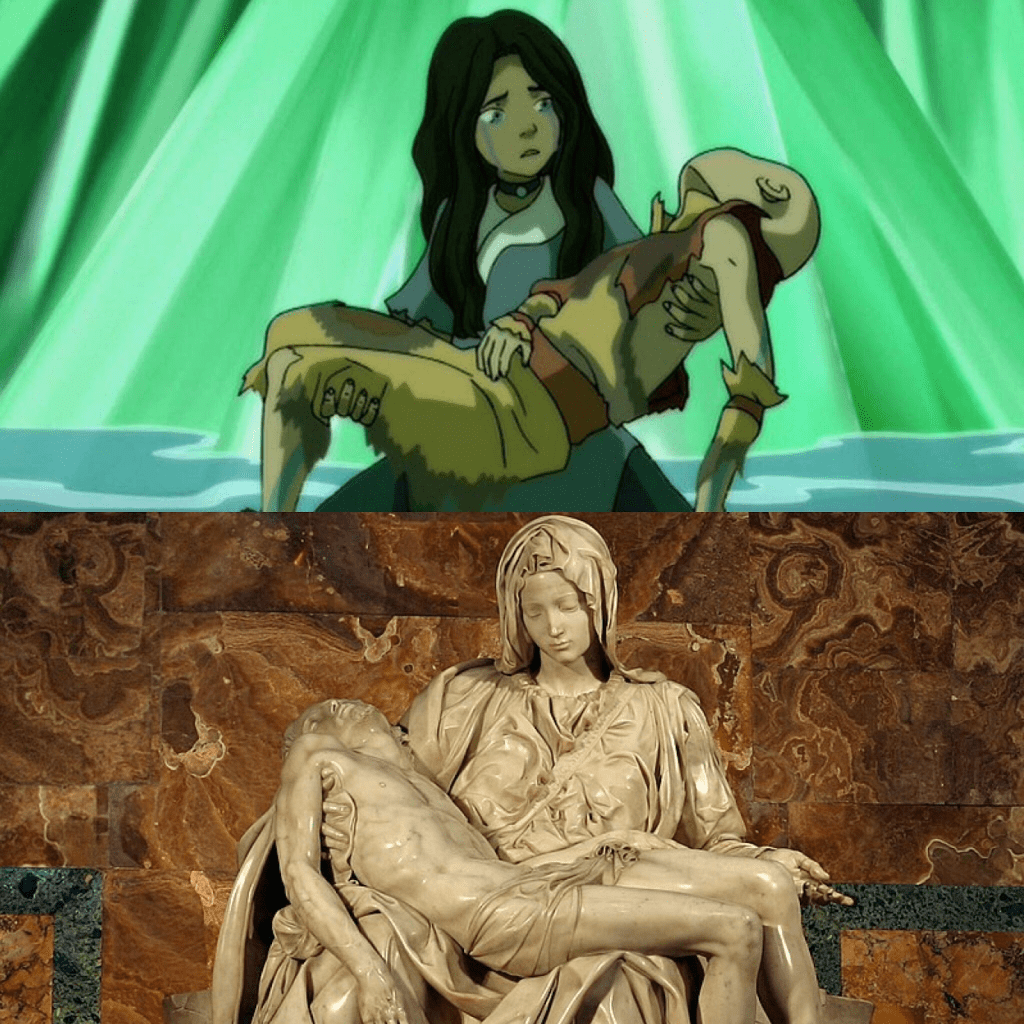

At the rising action of the show’s run, our gang has spent weeks in the surveillance state of Ba Sing Se surrounded by deniers of war, a violent underground police force, and the evolving threat of Azula, who seeks more than anyone now to capture the Avatar. In anticipation of battles to come, Aang seeks to master the Avatar state, where he learns he must release his worldly attachments, including his loved ones, to free all his chakras. This path, composed of sacrifice and suffering, mirrors the Passion, the last period of Jesus Christ’s life prior to his crucifixion. As this passion nears to a close, Aang is called once again to the salvation of his friends. In the heat of this battle, a turning point in the series, he faces off with Azula and Zuko following the latter’s betrayal of Aang and Uncle Iroh. In a last ditch effort at honor, Zuko rejects the peaceful life he’d found with his uncle in Ba Sing Se and fully embodies his role as Judas; the love of his father is his 30 pieces of silver. As Aang enters the Avatar state and forfeits his emotional attachment to Katara, representing Jesus’s severance from the human world, he is struck and killed by Azula, mirroring the crucifixion under Pontius Pilate. Katara is the only apostle at his crucifixion, playing both Mary and John as she collects Aang’s body, the scene animated to produce “Pieta,” or pity, the depiction of Mary holding Jesus’s mortal body after death. Contrary to the original story however, it is not a father who resurrects the savior, but a makeshift mother. It is Katara, with her healer’s hands and spirit water, who restores Aang, the show’s clear messaging about her role as his equal rather than a humble servant.

Top: Katara holding Aang after he is struck down (Season 2 Finale); Bottom: Michelangelo’s “Pieta.”

The plot itself is not the only similarity to the Bible, but the structure of storytelling. For instance, Aang’s story is told in three seasons, known as “books”: The Book of Water, The Book of Earth, and The Book of Fire. We can imagine The Book of Air would highlight his childhood, life before he was the Avatar. This mirrors the Gospel, the first four books of the new testament: The Book of Matthew, The Book of Mark, The Book of Luke, and The Book of John. Each tells the story of Jesus’s life and his role in the ministry, but notably there is very little to be said about his youth. In this way, “Avatar: The Last Airbender” only focuses on Aang as the savior.

Another striking parallel between the series and the events in the New Testament is the presence of deus ex machina, or “God from the machine.” This describes a plot device where some supernatural power or sudden change in the story serves as a solution to a previously unsolvable problem.

God, meet Lion Turtle. Lion Turtle, meet God.

As Jesus prepares for the salvation of sinners everywhere, onlookers expect a man’s death, a moment defined by finality. Jesus, however, knows that he will resurrect and rise up to God’s right hand side, and to a degree cannot be said as having given up everything in the face of death; he knows this moment does not signify the end of his life. Aang has a comparable experience when he finds he must surrender his pacifism to kill Firelord Ozai, as it’s the only way to end the Fire Nation’s reign. Calling on his past lives, he is consistently met with the same answer: sometimes, we have to sacrifice pieces of ourselves for the greater good. Dealing with the anguish of this answer, Aang meets the Lion Turtle, a deity that we have previously never met. The Lion Turtle bestows upon Aang the ability to energy bend, something no human has ever done, allowing him to take Ozai’s bending without taking his life. With this solution Aang fulfills the prophecy of salvation, taking solace in the security of his spiritual beliefs. Akin to Christ’s crucifixion, he holds onto personal safeties and therefore has not sacrificed himself totally either. In the end, world peace comes at the price of Aang’s peace of mind.

Blood of the Covenant

Focusing on the applications of religious parallels in the series’ storytelling, the most prevalent cinematic trope is found family. As a result of the war at the base of the show’s plot, each and every character we meet is running towards or away from something, never staying in place, and rarely connected to family for long. The exceptions to this are siblings Katara and Sokka, and Zuko accompanied by his Uncle Iroh. The writers consistently highlight themes of community, chosen family, and the value of connecting to those around you. An important caveat, however, is that the success of these connections is circumstantial.

Aang meets Katara and Sokka, two teenagers who have lost their role models at home, their mother dead and their father off to fight in the war. As a result, they must step up and behave like responsible, rational adults, or as close to that as you can get at 14 years old. They have already lived difficult lives, caring not just for themselves but the members of their tribe, and so they’re better equipped to handle the moral and practical challenges ahead of them. Comparatively, Jett and his gang, the only other group of unsupervised children in the series, are not quite so well adjusted. Jett’s friends serve a foil to Aang and his; another found family “helping” to bring balance to the war in a way they understand. While Aang has a duty to the world as Avatar, Jett’s obligation is self-inflicted after his own experiences with the Fire Nation. When he happens upon so many other kids looking for a sense of stability, he provides it the way he knows how. Destroying entire towns just to kill the Fire Nation soldiers inside, in his own way Jett weighs sacrifice with results, each of our group leaders fighting for their own “greater good.” His story mirrors Aang, indicating to the viewer how his journey could have turned out had he not found the right friends to take it with. Jett’s ending, an ambiguous and perhaps a fatal one, leaves us feeling disheartened, thinking about everything this spirited boy reminiscent of our protagonist might have done for the war effort after turning a new leaf.

By highlighting the bonds maintained between characters in their darkest hours, the writers spotlight the people we choose to love and their ability to shape our development. In this context, friendships signify a covenant, elucidating that our connection is not only with each other but also with our own spirituality. The sacred covenant is sealed by blood, as Moses sprayed animal blood on his people and Jesus offered his body and blood in the form of wine and bread to solidify a promise to God. Parallels can be drawn to how Aang builds up his relationships with the Avatars before him and the spirit world, bringing that same holy promise of his past lives forward to the people of Earth. The theme of a binding spiritual relationship mirrors increasing loyalty for Aang, who even witnesses his own body consumed as Aang shaped cookies for Avatar day celebrations, a clear play on the soft and simple dough given during Communion.

Left: Communion wafers; Right: Avatar Day cookies

The Impact of War on Children

For all intents and purposes, Aang’s story is Jesus’s, except for one big difference: Jesus and the apostles were not children. At the end of the day, our main characters are just kids trying to do their best; as their maturity increases, this fact becomes more glaring. The characters around Aang, primarily his three main apostles, slowly learn and grow into themselves while teaching Aang most of what he needs to be the Avatar. Despite being a repeatedly reincarnated soul, his body and mind are young and must be nurtured. There is an equal exchange of knowledge within the show’s friendships, communicating that Aang is not above the experiences of childhood with Sokka, Katara, and Toph.

Nowhere do they feel more youthful than in Ba Sing Se, where the war only exists outside those walls. Far into their journey and following so many battles, we’d expect our gang to seem more grown up, but beyond the concern of combat, they’re free to act as they please. Zuko goes on dates and keeps a part time job with his uncle. Katara and Toph have a girls’ day with spa treatments and makeovers. Sokka learns Haiku to impress girls. The false sense of security gives us a glimpse at who these kids would be without the war. It’s heartbreaking and even though you know it’s not real, you want them to enjoy it for just a little longer. To be kids for just a little longer.

But our main kids aren’t the only ones thinking they’re free to be young. The most revealing narrative is when they reconnect with Jett and the remainder of his friends in Ba Sing Se. Jett is now more apparently a child than ever. He fights honestly, promising his friends they’ll do things the right way. The young hothead with a chip on his shoulder is now a teenage boy looking for a quiet, honest life, but he’s too young and naive to realize that honesty is what will lead to his own demise. The Ba Sing Se arc illustrates most clearly how war affects children and shapes religion.

Historically, war warps cultural and religious traditions, either weaponizing or destroying them. This has been profoundly true for the Palestinian conflict of the last several decades, and especially since 2023. These ruthless realities have displaced countless families and left over 40,000 children deprived of one or both parents as per UNICEF’s estimates earlier this year. These children, much like the fictional characters we’ve come to love, now face the world alone, forced to adapt to a violent climate and grow up much sooner than is fair. The themes of spiritual divide and war on peace in “Avatar: The Last Airbender” are especially reflected in the destruction of holy spaces, most notably the bombing of Bethlehem in December of 2023. This moment, framed by attacks on the Christian deity’s birthplace preceding the celebration of his birth, clearly indicates how the atrocities of our global conflicts are so succinctly communicated through children’s media. Messages of empathy, community, and a responsibility to take action are vital for all members of society, but in an age where “unprecedented times” begin to shape our precedents, “Avatar: The Last Airbender” takes on the onus of guiding young children through them.